On February 22, 2023 Google announced the sunset of Coding Competitions. This marks the end of the road for Hash Code , a team programming competition I co-created @ Google France in 2014 and led through 9 annual editions.

What was Hash Code?

Hash Code was a team programming competitions organized by Google, with local hubs independently organized by universities and developer groups around the world.

The KU Leuven #hashcode hub is ready to participate with a full house tonight! Good luck to all teams! #kuleuven #hype pic.twitter.com/avVYxZ8nfC

— Thomas De Backer (@mosterdt) March 1, 2018

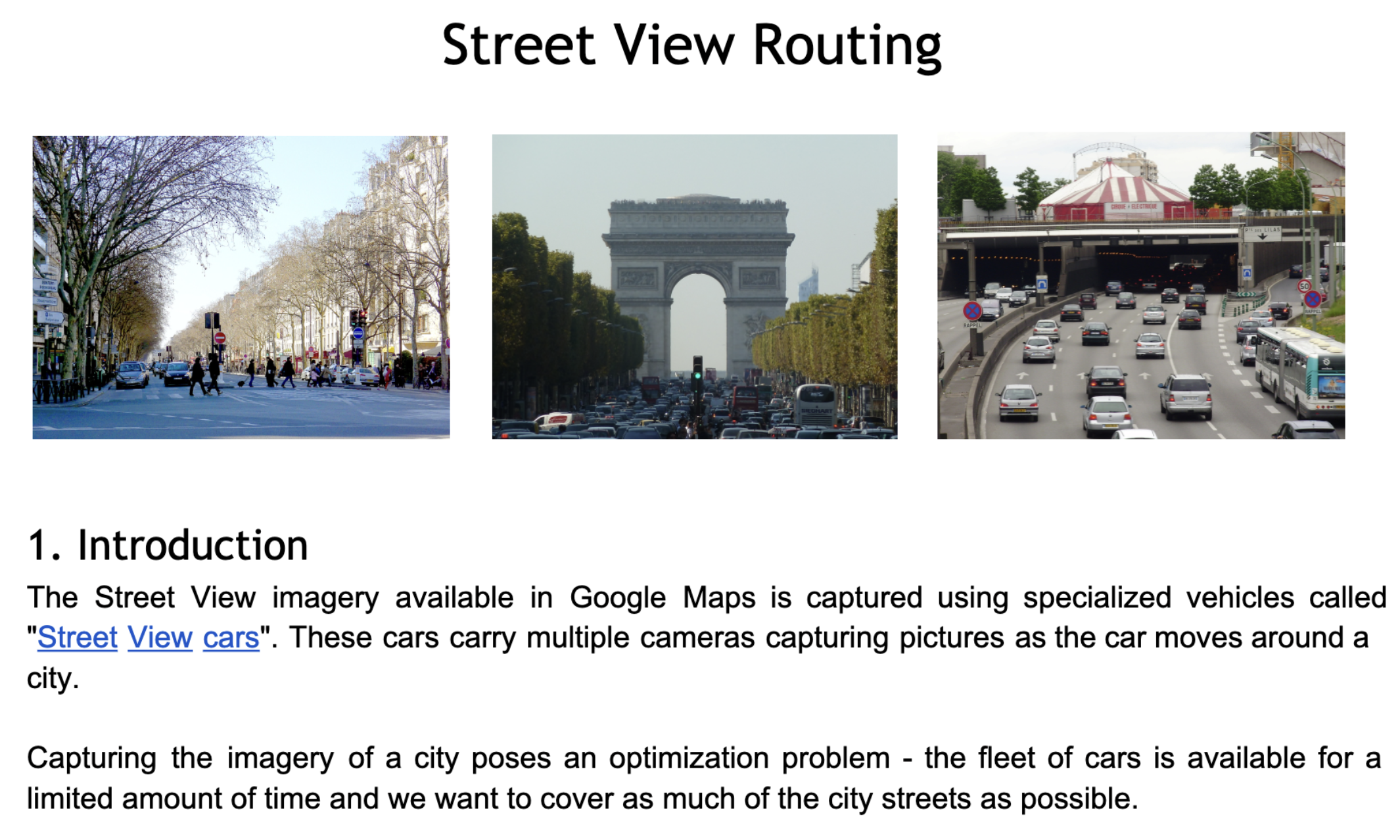

The problems were inspired by actual challenges faced by Software Engineers at the company. For example, the very first Hash Code problem was optimizing the routes of Street View cars capturing imagery of a city: it was something my colleagues at Google France were indeed working on at a time.

I think people liked it (and we the organizers liked running it), because of the community-building experience it was providing.

This was happening at three levels:

- the contestants worked in teams of 2-4 people. It feels good to work together, and each Hash Code edition gave the participants an opportunity to practice teamwork.

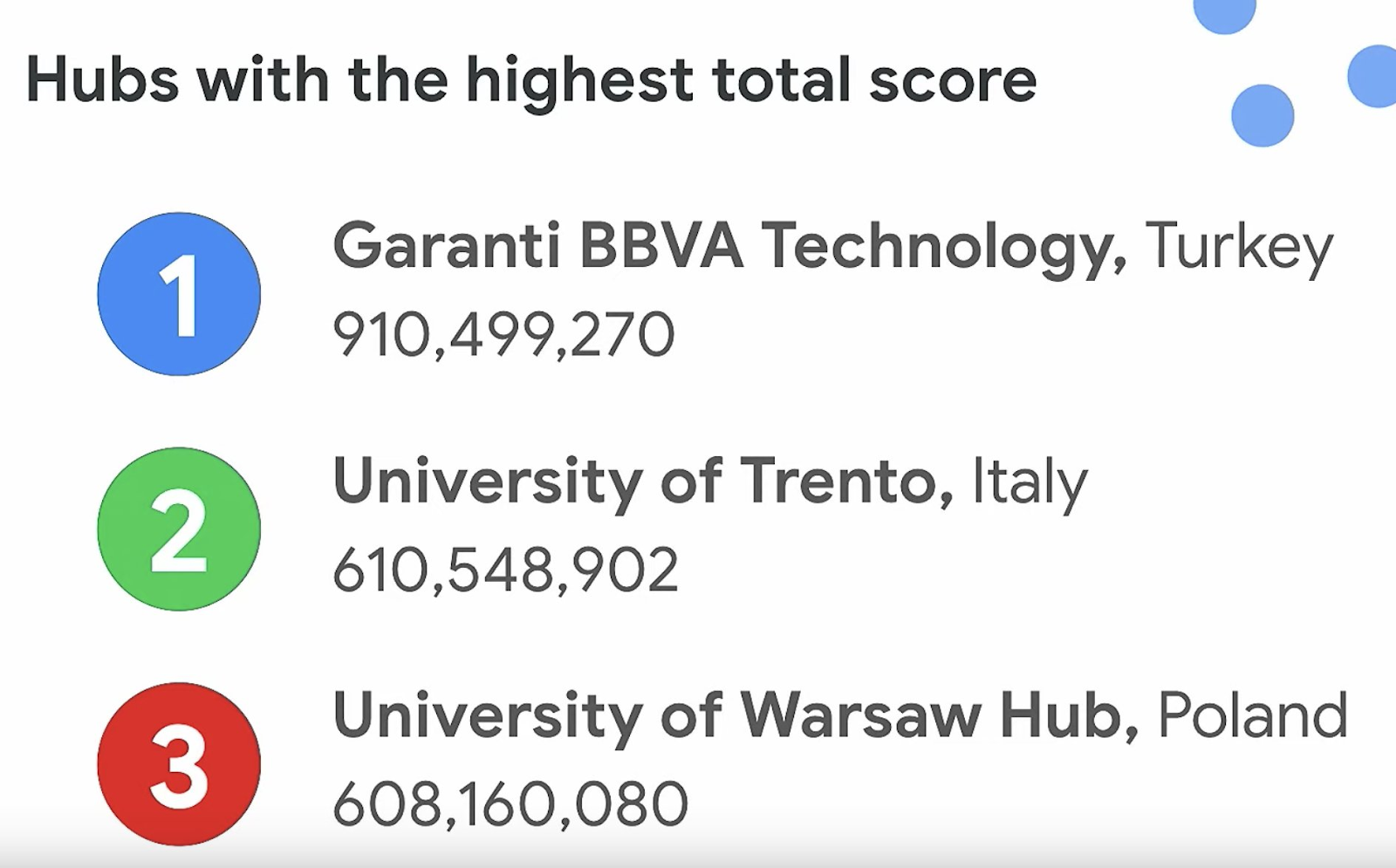

- the teams gathered in hubs, which were self-organized local meetups (in-person or virtual), typically run at a university or a developer group. This created a feeling of representing a local community together, and allowed everyone to meet like-minded people from their area or school.

- we only had one big online round each year, and everyone was working on the same problem at the same time. So beyond teamwork in one team, beyond the local vibe of a hub, there was also a sense of participating in a global event at the same time as thousands of other developers around the world

Quick pizza break and back to hacking @Andela_Kenya @Andela #hashcode2016 pic.twitter.com/LZpnzQRqnK

— Anthony Nandaa (@ProfNandaa) February 11, 2016

My favorite ranking of each Hash Code was the ranking of hubs by total score. Adding the score of all the hub participants together wasn’t of course a very fair metric (as it favored bigger hubs). But it was a quintessential Hash Code thing, we were looking at the total and not the average, because this way every single participating team always helped their hub standing, even if they only earned 1 point.

The last few competitions had over 100k participants each, and were probably the biggest programming event of this type in the world 💫.

Problem archive

We set up a problem archive on GitHub. For my personal favorites, check out these three:

- Street View routing (Hash Code 2014): the very first Hash Code problem, which defined the competition formula we followed for all the years to come. The problem statement was directly inspired by a real optimization problem our colleagues at Google France were working on at the moment.

- Data center reliability (Hash Code 2015): neat problem that captures fundamental concerns of building reliable systems from unreliable components: maximizing overall performance while planning for the inevitable failure of some components.

- Photo slideshow (Hash Code 2019): one of the shortest Hash Code problem statements, and a lot of its beauty is in this simplicity. All that the problem statement asks for is to arrange a set of photos into a sequence, and the problem is already NP-hard.

Competition history

The first edition (Hash Code 2014)

Registered participants: 200 (France-only)

Back in 2013, the engineering team at Google Paris was new, relatively small and growing fast. As a new kid in town, we felt we could benefit from more outreach, including building more connections with French students and universities. And what do you do when you want to build connections with someone? Obviously, you invite them over for a pizza-and-coding session!

But what should the coding session be about?

In a brainstorming session, we agreed on three pillars that ended up guiding Hash Code through all of its history:

- Accessible at all levels. We made Hash Code problems open-ended, so that it’s easy to develop a naive solution first, and iterate from there. This makes the competition problems accessible to participants at all levels, not only algorithm experts.

- Reasonably realistic. We made it a team event, because engineers usually work in teams.

- Scrappy. Hash Code started as a side-project for a few engineers, so we couldn’t build anything too fancy in terms of the competition setup. This is why in Hash Code you only needed to upload the resulting output of your program. We chose to focus more time on developing the competition problem and less time on the infrastructure.

We set up a website and sent an invitation to local universities. The first paragraph read:

At the time one of the engineering teams at Google Paris was working on optimizing routes of Street View cars taking imagery of a city. We took this idea and adapted it into Hash Code first competition problem .

Street View routing from Hash Code 2014

The event was a two-day affair, starting on Friday afternoon with an introduction ceremony and a practice round using a toy problem. The practice round was very useful: for the participants, it allowed every team to test their setup and test-run their teamwork a day before the competition. For the organizers, it gave us some reassurance that the infrastructure (electricity, WiFi) can handle the event load.

Hash Code 2014 in the Google France canteen

Saturday was the big day, and it was the test for all our merry preparations.

Things went well: the sound I remember the best was the silence of the canteen in which 200 intensely focused students worked on solving the Street View car routing problem. I also warmly remember a few tongue-in-cheek solutions created by the contestants – in one of them, the Street View cars were scheduled to drive routes that resembled the word “Google” when viewed from above ❤️. (This type of playfulness later became a bit less frequent during Hash Code onsite finals, as the competition expanded its reach and became more competitive.)

The author at Hash Code 2014

The one major issue we encountered was a pizza shortage. To estimate the amount of pizza needed we took the guidance from the office food team, and (given that it was an event for students who traditionally like pizza very much), we multiplied it my two. That was not enough. Based on the experience of Hash Code 2014 I now believe that the right pizza coefficient is around 3.5.

The event worked, the students were happy, we were happy, everyone had an appetite for more. We just had one major issue to resolve if we wanted to organize Hash Code again…

Technical issues (Hash Code 2015)

Registered participants: 1538 (France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Switzerland).

The main limitation of the first edition of Hash Code was the physical size of our office canteen – at 200 participants, the space was packed. Even more people had filled in the registration form and we sadly weren’t able to invite everyone.

In the second edition we wanted to enable everyone interested in Hash Code to participate. But we also wanted to preserve what made the first Hash Code fun – the feeling of a local community gathering. How can we make the competition bigger without sacrificing the local feel?

The solution we came up with is Hash Code “hubs”. We invited universities and developer groups across France to organize Hash Code events of their own at their own location (and with their own pizza 🍕). We provided the competition problem and the online scoring system – including a per-hub scoreboard, to help create an engaging local experience. The best scoring teams in the Qualification Round were to be invited for the Final Round at Google Paris.

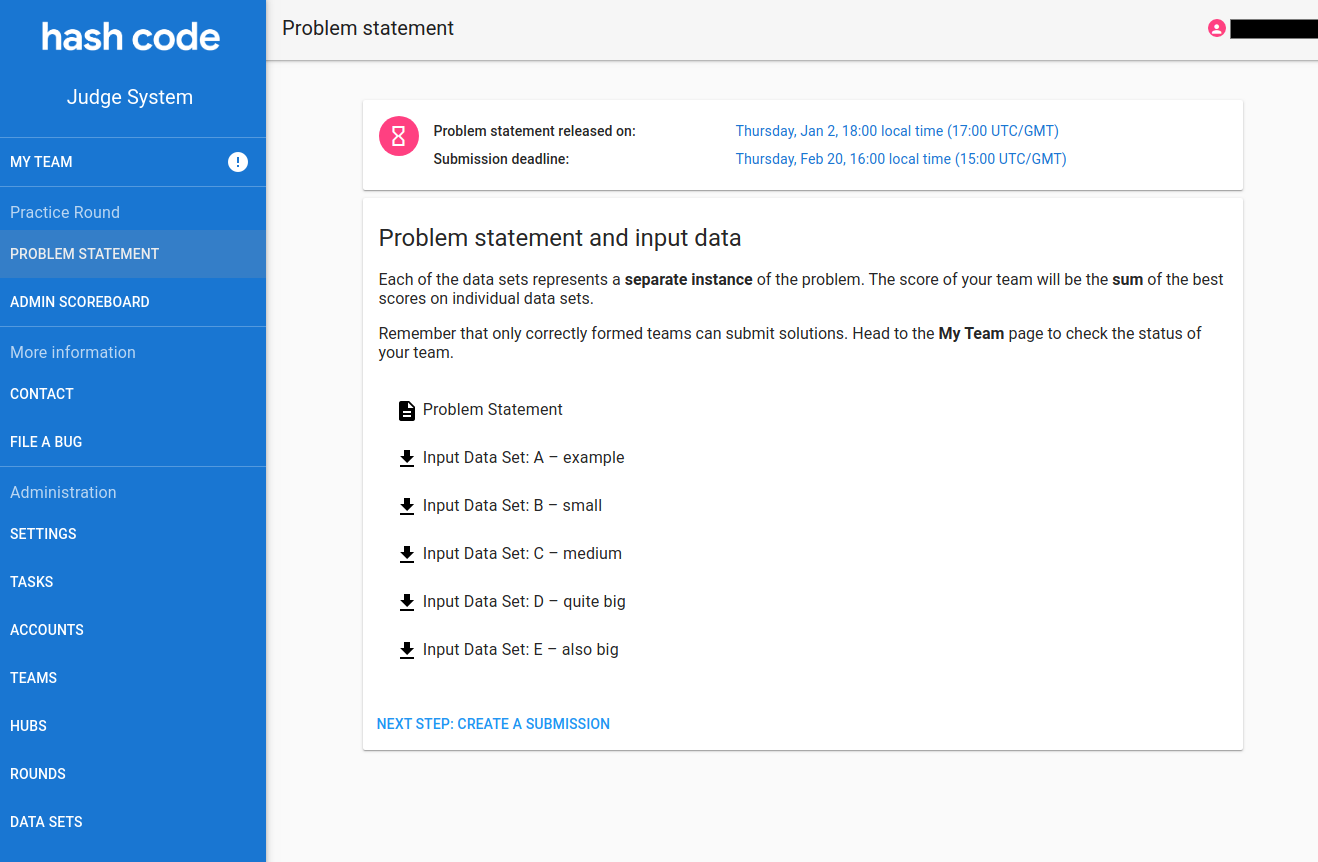

Adding the online Qualification Round was the single biggest change in the history of the competition. Because every year we have many more participants in the qualifications than we can invite for the finals, the Qualification Round is our top-of-mind priority and the make-or-break moment of each edition.

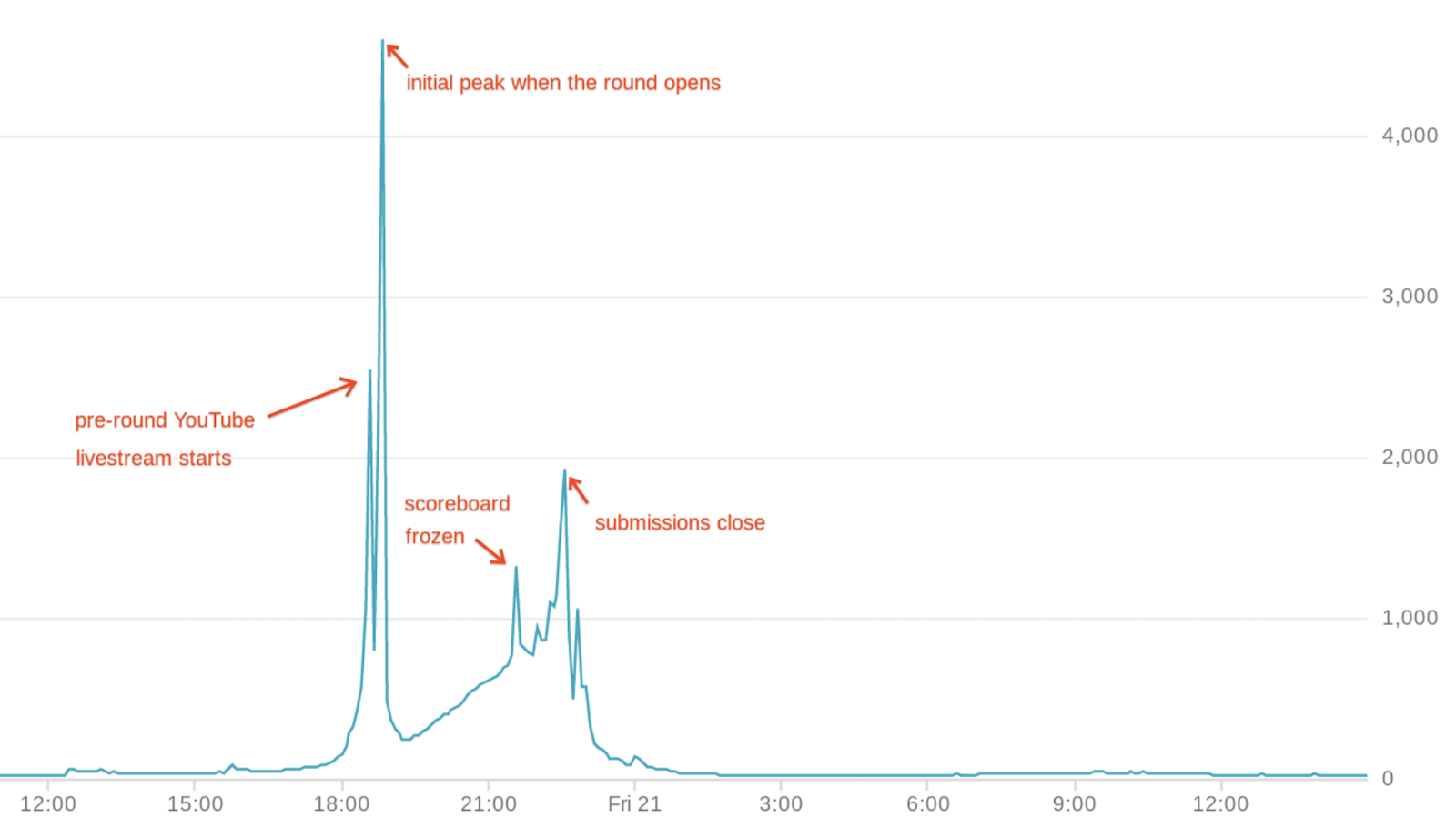

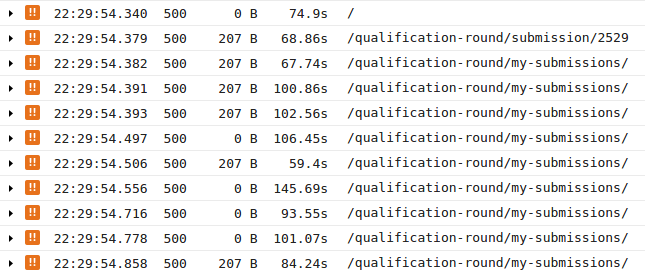

Now, speaking of breaking, the 2015 was also the year of our biggest technical issue to date (knock knock on my wooden desk). Our ad-hoc scoring system created a year earlier had scalability limitations (related to how the scoring application was using the underlying database) that we didn’t fully understand before the event. These limitations became apparent when ~1500 contestants attempted to submit solutions at the same time:

Server logs of the overloaded scoring system.

And to make this especially ironic, the competition problem we prepared for the round was about data center reliability. (to be fair, the breakage wasn’t because of a data center issue. It was purely a problem in the scoring system – more on this below ).

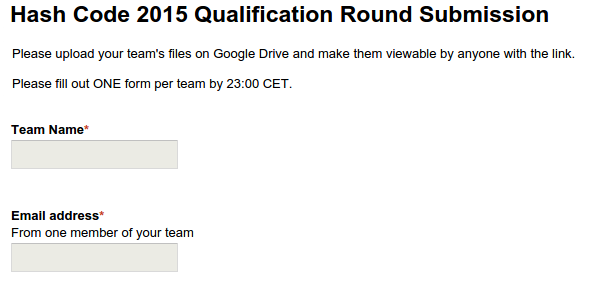

The evening was saved by a Google Form – we set up an emergency backup submission form that wasn’t scoring anything, but allowed the contestants to continue submitting their solutions to the competition problem. The next day we spent a pretty tense workday feeding those emergency-system submissions back to the scoring system and calculating the results.

Emergency backup submission form.

While the evening of the competition was very tense because of the breakage, we were reassured by the feedback from the participants and hub organizers – despite the glitch, people had a good time! On our side, we firmly resolved to be better prepared for the next year.

At least things worked correctly for the onsite Final Round, for which we prepared a fun problem about coordinating Loon balloons . These balloons don’t have a propulsion system, so the only way to control where they go is rely on different wind direction at different altitudes.

It was a lot of fun and balloons #HashCode2015 pic.twitter.com/Hl0Yxd8zJy

— Cecile (@CecileHbh) March 30, 2015

Scaling up (Hash Code 2016)

Registered participants: 17307 (EMEA).

For Hash Code 2016, we wanted to expand the competition geographically, for the first time inviting participants from most of the EMEA (Europe, the Middle East and Africa) region. With the technical issues of 2015 fresh in mind, we knew that we needed a bigger boat, that is – a scoring system that can scale.

Our original system was developed with a small event in mind, and we didn’t pay particular attention to scalability. The development stack we picked was a combination of a Python application running on App Engine, using a MySQL database as storage and the Django framework to link the database to the application. This is a pretty good stack, especially if the primary goal is development speed. It is also certainly possible to develop scalable applications on it – especially if you have relevant experience and know which pitfalls to avoid. We didn’t, and the scoring system was making too many database writes upon a visit, overloading our MySQL database during the Online Qualifications…

It was possible to mitigate the issue by reducing the number of database writes. But, as we were thinking about expanding Hash Code, we didn’t only want to only address the issues that come with the current expected load – we wanted to be ready for years to come.

So we got back to the drawing board and developed a new scoring system, still using App Engine to host the application (this part does scale very well) but now using Datastore as the backing database. Datastore is a database specialized in scalability – it has this beautiful property that things that would be slow in a traditional SQL database, are just impossible with Datastore. It means it’s harder to design and develop your application – but once you have it, it’s likely pretty scalable.

Developing this new system in the months before the 2016 competition in a small team on which everyone was a volunteer with limited time was challenging – but it was worth it, as the new system worked nicely not just for this, but for 6 full editions!

Of course, the scoring system was only one element of scaling Hash Code in 2016. We expanded the network of Hash Code hubs thanks to fantastic new hub organizers from across the EMEA who joined us that year. We also started to invest more in preparing Hash Code live streams – more on this below ).

Quick pizza break and back to hacking @Andela_Kenya @Andela #hashcode2016 pic.twitter.com/LZpnzQRqnK

— Anthony Nandaa (@ProfNandaa) February 11, 2016

Iterate (Hash Code 2017)

Registered participants: 26420 (EMEA).

Now that we had the new competition system in place, 2017 edition was when we caught a breath launched a few pragmatic quality-of-life improvements. This included a push-notification banner (handy if we need to announce a problem statement clarification or react to technical issues), per-country scoreboards, a new experience for hub managers and – behind the scenes – more automated testing.

On the problem development side, we focused the Qualification Round problem easy to understand. After what we felt was a pretty tough Delivery drone routing problem in 2016, this time we run a neat optimization task about caching YouTube videos , increasing the number of teams who submitted a solution by 3x!

To celebrate the theme of pizza, we also ran a practice problem where the challenge was to optimally cut pizza into slices 🍕.

Seems that someone is cutting pizza... 🍕 #hashcode2017 #ready4hashcode @Google pic.twitter.com/EHCGzXfD7x

— Ana Roig Jiménez (@anicacortes) February 16, 2017

Road to Dublin (Hash Code 2018)

Registered participants: 37778 (EMEA)

In 2018 we ran a Qualification Round competition problem inspired by self-driving cars , which was one of the hottest topics of the time.

As the office event space at Google France was closed for renovation works, we needed to find a new home for the competition finals. We settled on Google Dublin, one of the company’s biggest offices in EMEA and ran a problem about urban planning , a reference to the newly re-architected Grand Canal Dock area where the Google office in Dublin is based.

Another first for Hash Code: two of Google Dublin volunteers who came to help with the Final Round in 2018 met during the event, and later got married in the summer of 2021 ❤️.

Going global (Hash Code 2019)

Registered participants: 70865

By 2019 we had been discussing the if, the how and the when of going global for at least 3 years.

After long discussions about the logistics, we agreed that the signature property of Hash Code we want to preserve is the “unity of time”: the feeling of participating together in one intense, but approachable event. This determined everything else.

For the event to stay approachable, we needed to keep the original formula of a 4h programming round (longer programming marathons are less appealing to beginners) and to preserve the unity of time, we needed to stick with a single Qualification Round.

On 28 February 2019, Hash Code became a global programming competition! We ran a fun, easy-to-explain problem about arranging a photo gallery in the most “interesting” way possible (see the problem statement to find out what that means:)). We were happy to see that the problem was approachable – the best type of posts I personally look forward to is feedback from people who participated in Hash Code for the first time:

Last week I took part with @KinnzaZ in a coding competition (#hashcode ) for the first time.

— Dalia Simons (@SimonsDalia) March 7, 2019

It was a blast, we failed and I wrote a new post about it: https://t.co/KAt0n3A8Xt

A big thanx to @Baot_IL for introducing us to this competition and hosting a hub #hashcodesolved

Virtual finals (Hash Code 2020)

Registered participants: 111955

By 2020 our scoring system was battle-tested. We also had a pretty stable set of processes to manage the competition that we’ve been developing over the years, including a handy list of backup solutions in case something goes wrong. This list included some pretty unlikely scenarios such as loss of power in the office.

But, our emergency plans didn’t include the one issue we encountered during the Qualification Round on February 20, right after the submission window closed. YouTube live streaming system had a very short (and rare!) outage , precisely during our livestream show in which we wanted to announce the results. What were the chances of that happening? 😅 We could hardly believe it when we realized that the stream isn’t working.

Livestream control room

Fortunately, this was not a critical part of the event – we simply unfroze the scoreboard (making preliminary results visible) and sent the livestream recording link to everyone via email.

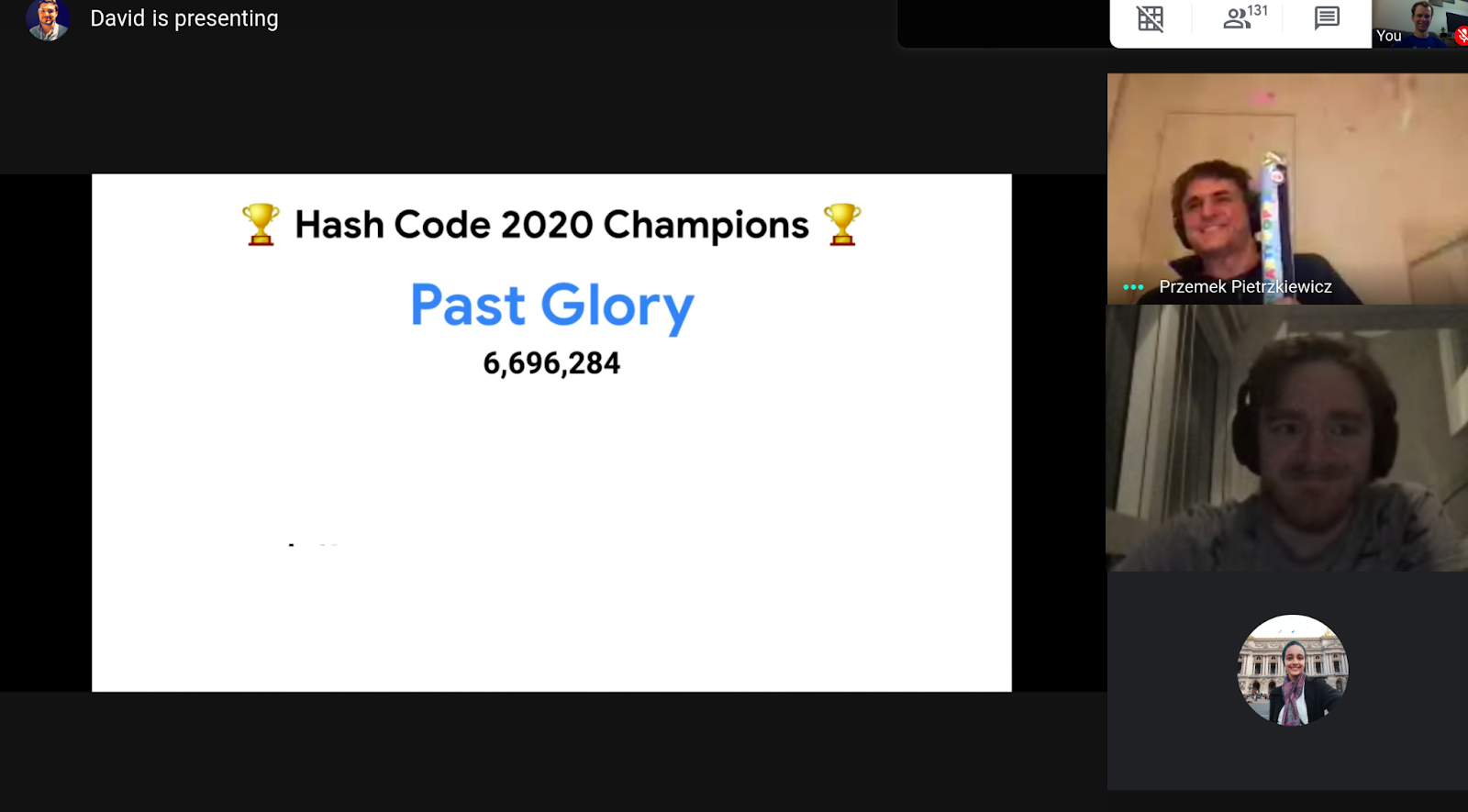

The 2020 finals were planned to take place in Dublin 🇮🇪 for the third time. But before then, the pandemic struck and for the first time we needed to pivot the finals to take place online. For me, I got to participate in the Hash Code closing ceremony… from my bedroom. In the end we got some very nice messages from the contestants who were understanding of the situation and wanted to let us know they still had a great time ❤️.

Virtual World Finals announcement call with the participants

Virtual hubs (Hash Code 2021)

Registered participants: 128410

The 2021 edition was even more affected by the pandemic than the previous one. Due to the ongoing disruption and risk created by Covid in most geographies, we didn’t want to take or encourage unnecessary risks and switched the Qualification Round hubs to a virtual-only model.

For the competition problems, we intentionally picked two topics not not related to the pandemic: city traffic lights and organizing software projects. With all the disruption and hardship created by Covid we wanted to offer an opportunity to think about and work on something unrelated.

Max & David, enthusiastic announcers of the Qualification Round results

The Hash Code community showed up more than ever before, reaching 111 000 registered contestants!

New competition platform (Hash Code 2022)

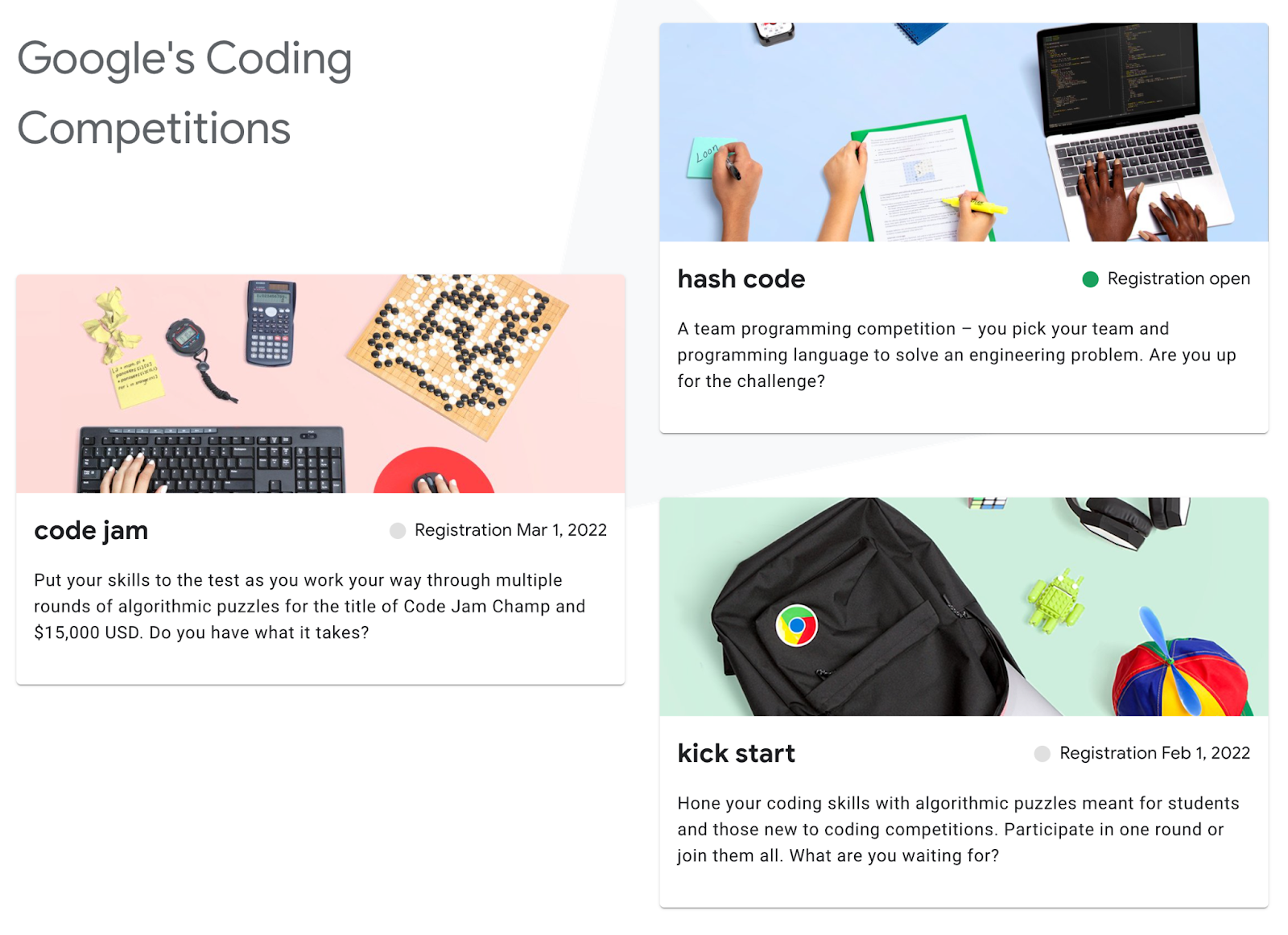

In 2022, we finished a big unification of the Coding Competitions stacks at Google.

Coding Competitions was a set of three annual programming contests run by Google, each with a different format. Code Jam was focused on algorithmic puzzles, Kick Start was designed for beginners, Hash Code was a team competition focused on heuristics for computationally hard problems.

The three competitions started off independently (Hash Code in France, Kick Start in APAC, Code Jam in the US) and as they grew they were eventually combined under one global program, running in a unified competition system.

The unified website of Google’s Coding Competitions

The new competition system had a few advantages:

- it offered a more integrated experience for the participants, who no longer needed to switch between two websites (one for registration and another to compete)

- internally, it reduced duplicate work: the Coding Competitions infrastructure was developed by a dedicated team, freeing the Hash Code volunteers to focus on competition problems and other aspects unique to Hash Code

The sunset (2023)

Coding Competitions were sunset in February 2023, as per Google Developers blog post .

Lessons learned

Start small and iterate. There was no way we’d even try to start a global programming competition as a side project at Google France in 2013. Why would we? But it was worth it to start a local event, tailored to what we needed at the moment, using the limited resources that we had. From there, Hash Code grew iteratively, allowing us to make changes, learn and adapt.

The secret ingredient was pizza. Each Hash Code edition needed a good competition problem and a scoring system to run the competition. But the secret ingredient was always pizza, by which I mean the community feeling behind the competition. It was the teamwork, the opportunity to meet new people, the local hub experience and the buzz on social media that ultimately made each event feel worthwhile.

Thank you

Thank you to everyone who made Hash Code possible, helping it grow and thrive over the years! Especially thank you to the hub organizers, Hash Code wouldn’t work without you.

Thank you to all my colleagues on the Hash Code team @ Google – for almost 10 years of working on Hash Code together, and to the many volunteers from various functions and geographies across Google.

A special callout is due to the tireless sponsor and organizer of the first editions of the event and the discoverer of the Hash Code pizza coefficient, engineering site lead for Google France, Vincent Simonet.

I will miss Hash Code and miss interacting with you all. I have no doubt though that the energy behind the competition will be put to great use in other endeavors. Have fun, take care and see you around in this small world!

(Photos in the article by courtesy of the Hash Code team, Mathias Kende and others.)