At a gas station near Brno 🇨🇿 in the summer of 2022, a couple of Polish hitchhikers ask us for a ride. It’s a busy highway gas station, many cars are stopping by, and yet the couple looks dejected.

We take the hitchhikers in. It turns out they had been trying to find a ride for 3 hours. Fifty different drivers approached, fifty times they were rejected. My car is too small (single driver in a Toyota Corolla). I have a dog and you’ll get an allergy (fortune-telling Dr House). I’m in a hurry.

The rise of hitchhiking

A man and woman hitchhiking near Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1936 ↪

For hitchhiking to work, you need drivers willing to give lifts and riders interested in getting one. Both conditions were comfortably met in the global West of the 1920s, when the term “hitchiking” entered dictionaries. For half a century, hitchhiking grew to become a mainstream cultural phenomenon:

The fall of hitchhiking

The decline of hitchhiking started in the 1970s, fuelled by:

- increasing car ownership (lower demand for rides)

- lower air travel costs (again, lower demand for rides)

- decreased trust in strangers on both sides (lower supply and lower demand)

By the 1990s, the Guardian declared that Hitching in Britain is clearly a thing of the past.

These reasons all make sense: the economic logic suggests that with lowering of the demand and the supply of hitched rides, there will be less hitchhiking.

The catch ⚠️

There’s something missing in this model of hitchhiking decline, though. It doesn’t explain the situation from the opening anecdote, and in general the difficulty of catching rides in rich “Western” countries in 2022.

When you try to hitchhike in Europe or North America today, the demand for the particular ride you’re trying to get is there. The potential drivers are, usually, abundant. So why is it hard to catch a ride? Decreased trust in strangers can be part of the explanation, but it’s implausible that all 50 drivers approached by the Brno hitchhikers took them for murderers or psychopats. Something else must be going on.

The feedback loop of broken empathy

The availability of rides relies on the drivers seeing hitchhiking as a reasonable, socially acceptable practice. This is helped by a sense of reciprocity: If you hitchhike yourself (or used to do it), or have friends who do, you’re more likely to feel empathy for the riders, and to pick them up.

The increase in car ownership that gained speed in the 1970s meant that fewer and fewer people had the first-hard experience of catching rides, or just ever needing one. This reduced the potential for empathy between drivers and riders.

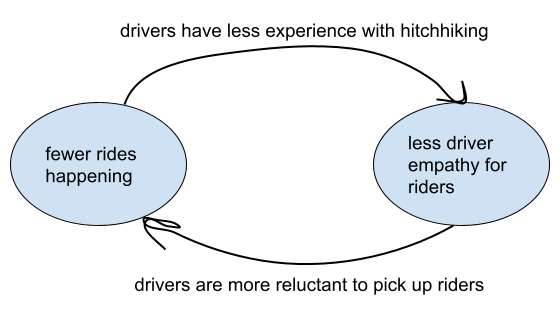

And it gets worse from here! Once empathy for the riders decreases and drivers become less likely to pick them up, this further fuels the empathy gap: because there are fewer rides happening, even fewer drivers get any experience of hitchhiking, including second-hand experience (hearing a friend say hi Joe I picked up a hitchhiker yesterday and they totally didn’t murder me).

It’s a negative feedback loop. The increased car ownership didn’t just lower the demand for rides. It unleashed a negative feedback loop of broken empathy, which ultimately killed the supply side of hitch-hiking.

The illusion of self-reliance

With this in mind, we can try to understand what’s happening in the minds of those 50 drivers who didn’t want to pick up the hitchhikers from Brno. They drive their own car. They never hitchhiked themselves. They don’t see why anyone would. After all, there are cheap bus transportation options, blablacar/ridesharing, affordable flights, etc. They likely think of themselves as self-reliant and don’t see why the hitchhikers would choose to end up stranded at a gas station, at the mercy of drivers. That makes them suspicious: the riders may be everything-D: deranged, degenerate, dangerous, desperate.

This sense of self-reliance feels good, but tends to be delusional, as beautifully captured in the cartoon strip “On the plate” (check out the full version ):

From “On a plate” cartoon strip. ↪

Is economic prosperity turning us into jerks?

Maybe. Economic prosperity brings the everyday practical comfort of not needing to rely on favors to get by. Teo You Yenn writes about this in 📖 This is what inequality looks like , a collection of essays on inequality in Singapore: low-income workers tend to rely on strong support networks of neighbors, acquaintances, friends and extended family to get by. High-income workers tend to pay for services (such as child care, cleaning, laundry, etc.) to have more flexibility and control of their time, so that they don’t need favors.

Relying on favors in your own life creates a sense of reciprocity and obligation that means you’ll naturally tend to help others, esp. where you can do this at little inconvenience to yourself. This is because human societies tend to shun freeloaders: we have a built-in instinct to give back. Yuval Noah Harari in 📖 Sapiens notes that gossip likely developed to protect societies from freeloaders (people who tend to receive favors but not to give them).

It feels good to help others, and it feels good to receive what we see as disinterested help. This can be seen in the starry eyes of Western backpackers returning from trips to developing countries, raving about the kindness and hospitality they experienced (and maybe about how easy it is to hitch a ride in Uzbekistan or Thailand). And yet we let our instinct for helping strangers out atrophy and disappear as the economic prosperity increases.

Conclusion

We should be hitchhiking more, and telling our friends about it (this blog post is a form of this for me:)). That’s something we can do to bridge the empathy gap for people around us, and to work on our own empathy muscles.

Friendly couple who gave me a lift in Thailand, Nov 2022.

Safe travels!